Piloting Citizen Science in Prison Gardens

People in prison are taking part in real science in collaboration with UC Davis researchers.

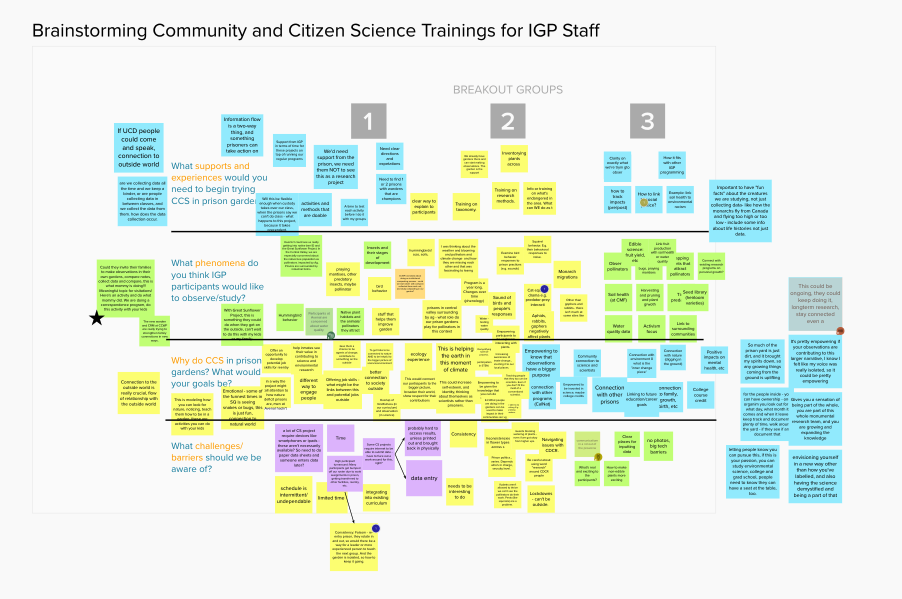

Since 2019 our team at the Center for Community and Citizen Science has been exploring ways that incarcerated people could do science in prisons, working with our partner, the Insight Garden Program (IGP). We sought funding from the UC Davis Public Impact Research Initiative to lay the groundwork for incorporating citizen science into IGP’s existing garden-based educational programming in regional prisons. We knew from our experience working in school gardens that we could find simple protocols that incarcerated people could use to collect and contribute data on pollinators, birds and other biodiversity, with minimal equipment and little training needed. However, we also knew that there are many constraints that come with working in prisons. We would have to learn from IGP staff on multiple levels:

- What will be interesting and worthwhile for participants?

- What is possible in a two-hour session?

- How do our proposed activities relate to various elements of the IGP curriculum?

- What rules will guide use of basic equipment such as clipboards, stopwatches and paper handouts?

- What can and can’t be brought into a prison for an educational program?

Our aim was to explore these questions with IGP staff, and with direct input from incarcerated people participating in the IGP program.

What is citizen science?

With citizen science, people can engage in scientific research through activities such as collecting data, conducting analyses, sharing findings, mentoring colleagues and designing novel investigations. Our own research shows that citizen science has the potential to deepen learning, leading participants to create change in their lives, landscapes and communities.

What does the Insight Garden Project do?

People who are incarcerated live in dehumanizing conditions, lacking access to programs and opportunities for self-enrichment and mental health benefits, work and life skills, and connections to others. For more than 20 years, IGP has been delivering an environmental education curriculum through which people who are incarcerated lead the design, creation, and cultivation of permaculture gardens. Through this work they deepen social and emotional skills, and prepare for reentry as empowered environmental stewards. In close collaboration with IGP, we developed a pilot project that would allow us to test out garden-based citizen science in prisons, carried out by IGP participants.

Why do citizen science with people in prisons?

Research and our own experience – multiple listening sessions at prisons in California – have shown that incarcerated people are interested in science, desire more opportunities for hands-on science learning, and respond positively to the notion of taking part in real science that also involves participants beyond prison walls (e.g., other volunteers and professional scientists). Furthermore, developing science knowledge and skills can foster marketable skill sets for incarcerated people, which they may use to analyze and directly address environment- and science-related challenges in their communities and for lifelong learning and literacy in science

We also view citizen science as one way to expand the boundaries of science, challenging traditional notions of who can participate in, shape, and use science, not to mention its resources and institutions.

But doing this takes an explicit effort. Citizen science is often seen as a promising way to address broad and persistent inequities in the science system, but in fact many existing citizen science programs do not reflect societal diversity and fail to reach marginalized communities. Working in prisons is one way to push against that reality, and begin realizing the full potential of what citizen science can be.

While this was useful progress, significant time passed before we could be allowed into a prison. The COVID pandemic hit prisons especially hard, not only in terms of high infection rates and limited medical resources, but also in terms of the intensity of isolation and the associated tolls on emotional and mental well-being. When access finally became possible, IGP staff were understandably focused intensely on the pressing business of spinning their core curriculum back up, while also maintaining the ramped up re-entry program that had gained new momentum during the COVID-19 lockdown. It was clear we would need to wait longer, and that our own team would need to conduct the pilot activities in just a small number of prisons, in collaboration with one or two IGP staff who had particular interest and bandwidth to try things out.

The first opportunity came on a hot, windy day in June 2022, when we visited Avenal State Prison to meet IGP participants, introduce the idea of citizen science, and try out some pollinator monitoring in the garden. We were excited about the deep well of curiosity and inquiry that the men brought to this new activity, and about early indications that pollinator monitoring inspired new ways of seeing and appreciating garden spaces. Some men were interested in learning new facts about insects. Several others appreciated that pollinators choose to visit the garden, that something they built at a prison could recruit wild visitors. Some were excited to continue the activity and explore what they could learn from data over time, and about data from other places. As expected (indeed, as we hoped!), there were plenty of lessons learned about how to better support and facilitate this activity. These themes and others were echoed at two subsequent pollinator monitoring sessions with IGP programs at California Medical Facility (CMF) in December 2022 and California Healthcare Facility (CHCF) in January 2023. We came away with a deepened commitment to our long-term vision for this work.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Traveling to a prison to talk about biodiversity is a surreal experience. On one hand, these are austere and dehumanizing places, freighted with bureaucracy, hierarchy and barriers of all kinds.

On the other hand, in every facility we visit, we find curiosity, enthusiasm and a wealth of knowledge and experience that participants bring to the idea of doing science in such an unlikely environment.

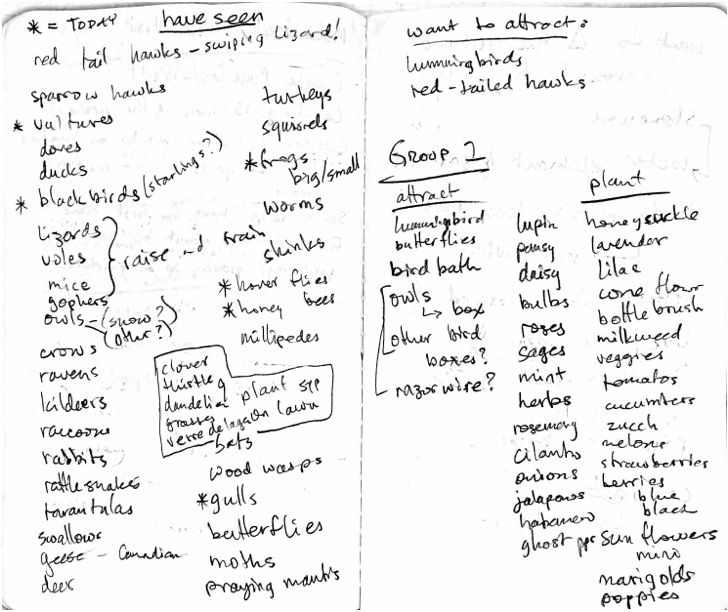

We always make extensive lists of the biodiversity that participants have seen around the prison yard, and just beyond the fences – all manner of birds, mammals, reptiles and insects. The notion of careful, intentional observation fits well in this setting, and the idea of contributing to something larger, and getting feedback about this real scientific work over time, is exciting to many.

We learned that this work is challenging. It takes commitment to plan and carry out these activities in the face of what feels like a million rules and requirements, some of which seem to pop up at random and without warning - which we note is part of a broader project of social control.

And yet, we also learned that citizen science in prisons is absolutely doable and worth doing. Each member of our team comes away from prison visits inspired and excited about what we could build with more resources and a scaled up program.

From here we have many short-term next steps. Our top priority is to learn what it will take to support citizen science activities that happen regularly, and sometimes without our presence. Our IGP partner working at CHCF in Stockton and CMF in Vacaville will be trying monthly observation sessions, and we will see how participation evolves. What do the men like or dislike about it as it becomes routine? What do they need in order to improve, and what do they want to do with their own data? What questions come up for them, and what other kinds of inquiry might be possible?

We have also learned that there is intense interest in birds for many of the participants, and we plan to add a bird monitoring protocol (as resources and bandwidth allow).

Our long-term goal for this collaboration is to establish a first-of-its-kind California program in which a statewide network of people in prisons advances science that has real meaning and impact for the participants themselves, and beyond prison walls for communities and the environment. Beyond the many benefits for participants, we hope this can help us learn more about the educational potential of citizen science, and provide collaborative opportunities for natural scientists who might want to work in a truly worthwhile context.

Learn more about their PIRI Grant Project

About the Authors

Ryan Meyer

Executive Director

Center for Community and Citizen Science

School of Education

Laci Gerhart

Assistant Professor of Teaching

Department of Evolution and Ecology

College of Biological Sciences

Chris Jadallah

Ph.D. Candidate

Science and Agricultural Education

School of Education

Heidi Ballard

Professor and Chancellor's Fellow

School of Education

Faculty Director

Center for Community and Citizen Science