Caves, Cacao, and Conservation Corridors

How public scholarship is inspiring the people of Guatemala to fight for their land and future

If you haven’t yet, read part one.

"There is a magic machine that sucks carbon out of the air, costs very little, and builds itself. It’s called a tree.” - George Monbiot and Greta Thunberg, in a new short film.

While Western scientists look for elusive magic bullets to solve climate change, they overlook opportunities to support Indigenous partners at the frontlines of forest defense and environmental restoration. Donors are oddly willing to fund quixotic projects like mechanical trees, while natural solutions like planting tree barely receive 2.5% of climate funding.

This is a travesty. Although Indigenous peoples make up just 5% of the global population, they defend 20 % of the earth’s surface and 80 % of its biodiversity. They often do so at high human rights risk. Global Witness has tracked the murder of environmental defenders for over a decade and an astounding two-fifths of grassroots martyrs have been Indigenous peoples.

Having had the honor of working and researching alongside some of Guatemala’s Q’eqchi’ Maya people for three decades, I have learned much from these passionate, dedicated people who, as Guatemala’s second largest Indigenous group, have vibrant, culturally-embedded strategies to slow global heating and regional drought. And, better yet, they are centered around cacao (kakaw), one of the few words in the English language derived from Mayan languages.

Environmental organizations have failed to include key partners

Climate literature abounds on the depressing tropical “D’s”—deforestation, degradation, and destruction—with very little attention to the “R’s”— recovery, regeneration, or reforestation processes — to heal the planetary damage already underway. Elite transnational biodiversity organizations like Conservation International myopically focused on defending protected areas from deforestation, while ignoring opportunities for partnerships with Indigenous peoples in surrounding rural areas. In the rare, protected areas where they endorse or support sustainable forest management, their experts in so-called environmental services tend to tout mahogany and other macho timber trees that have significant cash value for consumers and high carbon capture metrics. However, true climate justice must take into account the qualitative, usufruct values of other tropical tree species used in everyday life for ceremony, crafts, cuisine, health cures, communication with the spirit world, and other cultural uses.

Old-growth forests will likely continue to shrink due to an array of agro-industrial, logging, mining, drilling and other extractive pressures on parks. Given this, forest succession ecologist Robin Chazdon and others have drawn attention to secondary growth forests as an important zone of biodiversity research, policy intervention and climate solutions. If local people are invested in restoring them, secondary rainforests are resilient. No matter what keystone species are planted to initiate forest regrowth, diversity will inherently return.

In Guatemala, it’s past time to plant trees. Despite millions of dollars invested into secular, sustainable development projects since the creation of the 1.6-million-hectare Maya Biosphere Reserve in 1992 in northern Guatemala, most state-run parks are overrun by oil companies, drug cartels, cattle ranchers, and displaced colonists. Outside the protected areas, these same land grabbers have converted more than half of small farmer agricultural land into denuded cattle and oil palm plantations. Instead of going after the bad actors driving deforestation, the park service and organizations like Wildlife Conservation Society have demonized Q’eqchi’ farmers for their sustainable use of fire in swidden farming.

Value of the Forest

They have also failed to understand that Q’eqchi’ communities value the forests in different ways than people of mixed ethnic ancestry. In Q’eqchi’ ecological worldview, the most important species of the forests are not commercial trees like mahogany, but spiritually important trees like cacao, copal incense, edible trees like breadnut and other wild foods like palm hearts, artisanal materials and medicinal plants. Q’eqchi’ subsistence farmers recognize the micro-climate value of maintaining the village forests for, as they say, “hauling the rain” to their crops. When a family member becomes critically or chronically ill or when crops fail, Q’eqchi’ people seek ceremonial healing in sacred forested places. Planting ceremonies held in sacred sites are an essential element of traditional land governance.

Caves of Connections

Usually, these places of connection to the spiritual world are caves; but, they can also be natural springs, minor archaeological sites, cairns, incense groves and sunken wells called cenotes. Around these natural wonders, Q'eqchi' farmers traditionally conserved communal forests as a sanctuary for their mountain/valley spirits, the Tzuultaq’a. These areas are not secret, per se, but one does need to have some cultural competency and Q'eqchi' language skills to discuss them.

As a result of a failed World Bank project described in my first blog, lowland Q’eqchi’ villages lost at least half their sacred places to land grabbers between 1998-2007. The elders want those sacred sites back — buying the land on the open market if necessary. Often located on rocky soils or hilly places, sacred sites are not particularly arable, so the land grabbers may, in fact, be willing to sell them back to the community.

Villagers Make Declarations

In the meanwhile, since 2014, almost a hundred Q'eqchi' villages have declared themselves as "autonomous indigenous communities"—spanning almost 10% of Guatemala's land. Among other rights, these declarations give villages the legal standing to establish land trusts under Indigenous communal tenure. Although nearly impossible to win a communal title via national land laws, through clever use of Spanish colonial law still embedded in municipal governance, they can legally register village forests at the county level.

During the past five years, I have been working with a council of spiritual elders who govern a Q’eqchi’ rural social movement called ACDIP (The Indigenous Peasant Association for the Integrated Development of Petén). This Q’eqchi’ peasant federation represents a hundred autonomous villages, plus another 62 villages contemplating the shift to communal governance. Every one of these villages has one or more sacred sites, but certain communities have caves or altars that are more powerful sites that attract regional pilgrimage. In a slow process of workshop dialogues by day and dreams by night, ACDIP’s spiritual elders have prioritized a list of sacred places for reclamation along with an inventory of sacred trees for reforestation. These include incense, annatto (a spice for ceremonial foods), fruit trees, medicinal species, house building and craft timber, and—above all‚ cacao trees.

Cacao Cultivation

From the pre-Columbian period to the present, Q'eqchi' people have been known for their cacao cultivation and trade routes between the highlands and lowlands. When walking through Q'eqchi' territory, you can often stumble upon wild cacao groves around which the tropical forest has regrown. Local, feminist environmental organizations like my other ProPeten partners have been working with pilot Q'eqchi' communities to develop fair trade markets and products. Petenero Q'eqchi' chocolate is now winning competitions across Europe for the richness of its flavor.

What inspires me about this work is that the chocolate is not just for export to gringos. Should the international market collapse, national and local demand for cacao can easily sustain its price. Sold via traveling merchants who walk village to village, cacao is relished as an everyday drink (traditionally served black, unsweetened in a gourd blended with a bit of maize dough). It is also an essential offering to the hill spirits for permission to plant crops, blended with maize seeds before planting, and ritually shared in any community ceremony.

Respecting these cultural traditions, in the continued village mapping process described in my other PIRI blog, ACDIP's leaders and I hope to identify connected areas for cacao reforestation that could be the foundation for vernacular conservation corridors and climate resilience from below. Climate justice inherently requires centennial, if not millennial planning in partnerships with people for whom resilience is built into their culture and vision for a good life.

Projects from Cubicles Won’t Work

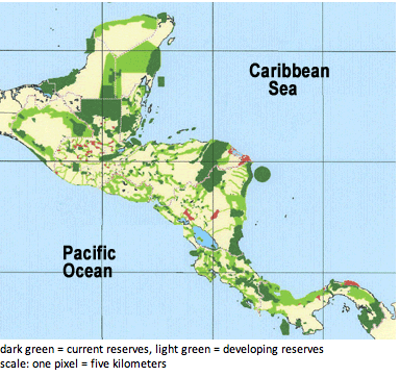

Climate projects hatched from cubicles won’t work. To give but one example of many failed World Bank paper projects, the Global Environmental Facility dumped $40 million between 1996 and 2005 into schemes to create a “Mesoamerican Biological Corridor” (MBC).

Excluded from planning processes, Central America’s Indigenous leaders perceived this as a top-down effort to disguise another set of infrastructure projects being funded to provide the gas pipelines, electricity, port, and road infrastructure to promote extractive industries and transnational shipping. A coalition of 50 Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and peasant organizations organized under the umbrella of a popular organization called ACICAFOC countered with a beautiful proposal for an “Indigenous and Peasant Biological Corridor." The World Bank bureaucrats blew the opportunity to invest in genuine grassroots transformation.

Missing the Forest for the Trees

Climate change is now upon us, and Central American farmers are suffering. As I sat down to write this blog, I wondered what the World Bank might be doing these days in Guatemala. Lo and behold, the Global Environmental Facility just approved a whopping $1.8 million in July 2021 for yet another paper project that will be spent flying consultants around to five-star hotels to monitor Guatemala's Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement. In an eye-glazing proposal, apparently, the plan is to create a "holistic system of MRV [measurement, reporting, and verification]" to "improve the quality of their NGHGI, just as that of their reports, monitor more closely mitigation and adaptation actions, national and international climate spending, and link to more effectively provided and received support to national policy priorities on climate change."

Talk about missing the forest for the trees! The planet is burning; but, take heart, it will be expertly verified "with accurate and official statistics and coherent activity data." With just a fraction of those funds, Q'eqchi' communities could reclaim and reforest all their sacred sites and create connective conservation corridors for the remaining protected areas.

Even in the best-case scenario that protected areas continue absorbing 11% of global carbon, current greenhouse gas emissions still outnumber forest sinks 10-to-1. The world needs ambitious and culturally appropriate plans for reforestation and natural succession. From Africa’s Wangari Maathei "green belt" in Kenya to Q'eqchi' visions of a chocolate forest, there is still time to support vernacular visions for climate justice. While the world's politicians dally at the United Nations Conference of Parties (COP), Indigenous peoples have holistic plans and accountable leadership structures that could immediately conserve and restore forests over this next critical decade of climate drawdown.

Learn more about their PIRI Grant Project

All blogs are the personal accounts and opinions of the individual writers and do not necessarily reflect the those of Public Scholarship and Engagement or UC Davis.