What’s in a Name

How public scholarship is inspiring the people of Guatemala to fight for their land and future

I confess, I hate acronyms. Many a brilliant social movement has been watered down by clunky names meant to impress donors, the state, or other bureaucratic actors. A name should be memorable—even better metaphoric—and convey the essence of the movement.

I learned this lesson from my first non-profit project called Remedios, meaning “cure” or “solution,” but that also had local historical meaning and a literary allusion to A Hundred Years of Solitude. It captured the imagination of a fellow Washington D.C. intern who, years later, remembered our evocative name later in his career distributing unrestricted, quarter-million dollar grants for women’s health. I thanked my 22-year old self for wrestling to find a name that resonated locally, nationally, and internationally.

The Power of Leftovers

So in 2011, when I was working with Q’eqchi’ leaders to write a proposal to the InterAmerican Foundation for territorial defense, I knew the name of our project mattered. I suggested we pick a name in Q’eqchi’ with cultural meaning and, after we brainstormed a bit, I said, “How about xeel?” (she-EL, meaning “the leftovers”). Xeel refers to a Q’eqchi’ practice of wrapping leftovers from ceremonial meals into green leaves to carry home to share with elders and children, so it has a deeper sense of reciprocity. ACDIP’s leaders chuckled that I knew about xeel, but none of us at that moment fathomed where it would lead us.

Speaking a Common Language of Data

But, before I tell that story. I should give some back history. I had just led a team in 2010 to document land grabbing that had occurred in northern Guatemala over the previous decade. I knew that if the World Bank was ever going to recognize the harm they had done to Q'eqchi' communities through their Land Administration Program and halt or redesign future projects to support Maya land governance, I knew we had to collect and present the data of dispossession in terms that Bank bureaucrats could understand. This meant a technocratic analysis of the property registry and cadastral maps.

However, I also knew from my work with the Maya movement in Belize how catalytic the Maya Atlas mapping project had been for their world-renowned movement for autonomy and Indigenous land governance. Although I had somehow convinced the Bank bureaucrats to pay for the technocratic study, we didn’t have a budget for community work.

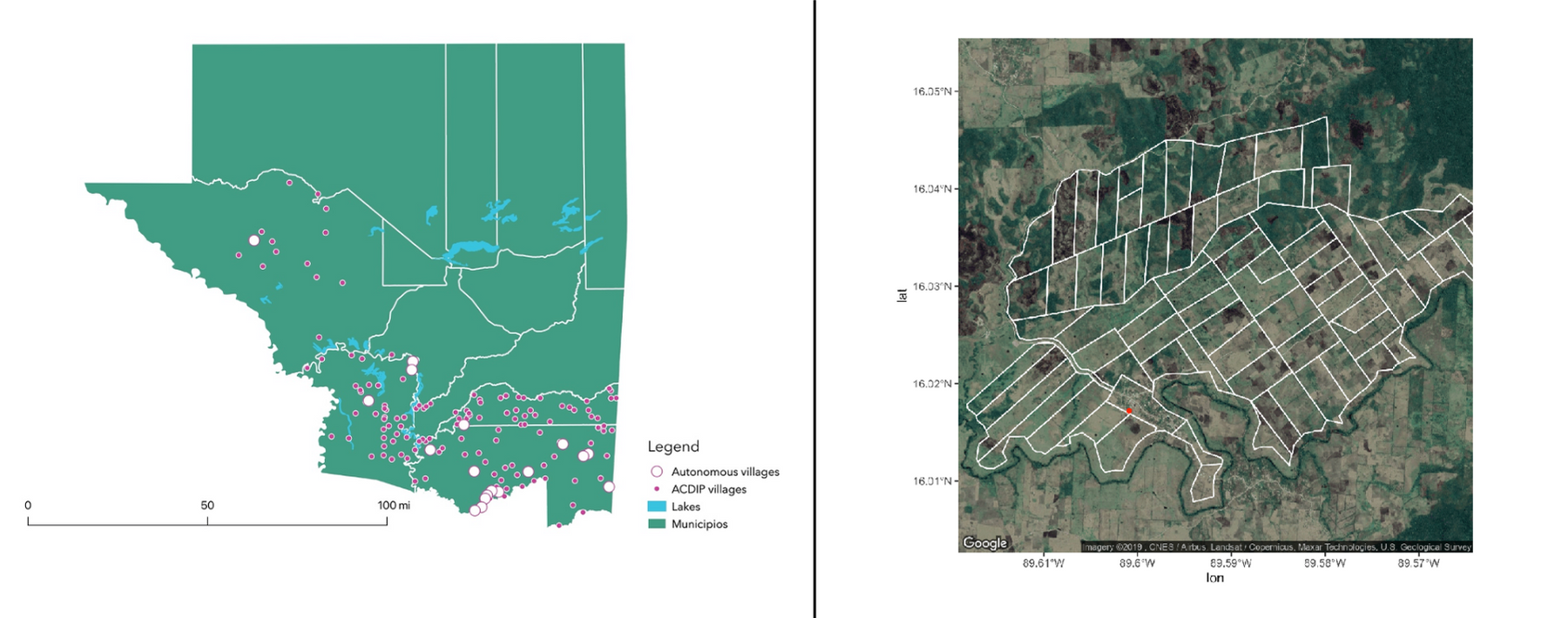

So, I cashed in my own symbolic capital and invited Q’eqchi’ leaders from a peasant federation Indigenous Peasant Association for the Integrated Development of Petén (ACDIP) to join our team and jiggled some money from the budget for travel and poster printing. My hunch was that village leaders could map their agrarian reality with equal or greater accuracy than what was recorded officially in government institutions.

The meetings we had with the 46 carefully sampled villages were transformative. While donors had spent tens-of-millions-of-dollars mapping agricultural lands, forests and protected areas, no one had ever bothered to share the land use or cadastral maps back to the villages! Overlaying the cadastre on overflight data of land use, my team created baseline images that village leaders marked in red (sold/stolen) or green (still under smallholder tenure). Local perceptions of village boundaries were profoundly different from what the government had demarcated.

We crunched the numbers and the villagers’ self-reported data of land sales concurred within a percentage point with the far more complex and expensive property analysis the Guatemalan GIS experts on my team had completed.

Recording Largest Land Grab Since Colonial Period

Put together, the results were shocking. Within five years of the close of the World Bank land titling project, 46 percent of smallholders had lost their parcels to land grabbers! It was a scale of dispossession not witnessed in Guatemala since the colonial period. To make a long story short, the World Bank attempted to question and censor our results through 13 so-called quality enhancement reviews at all levels of government, internal departments and external academic reviewers. Our data proved solid.

In the prolonged drama about whether or not the Bank bureaucrats would allow our report to go to press, a sympathetic program officer from the Inter-American Foundation grew interested in our plight and invited the Q’eqchi’ peasant federation to submit a proposal for Indigenous territorial defense.

ACDIP won three years of funding, then extended another two years, for territorial defense of Q’eqchi’ lands. Albeit modest compared to the operational budgets of NGOs, the grant was utterly transformative for a social movement. It’s easy to romanticize grassroots organizing, but activists do need some basic funds for cell phones, bus fare, food and lodging for meetings. With multi-year funding, they build momentum for a bigger vision. For the donor, this was the first time they had overtly supported an Indigenous social movement, and other allied Maya organizations subsequently benefited from this new direction of funding.

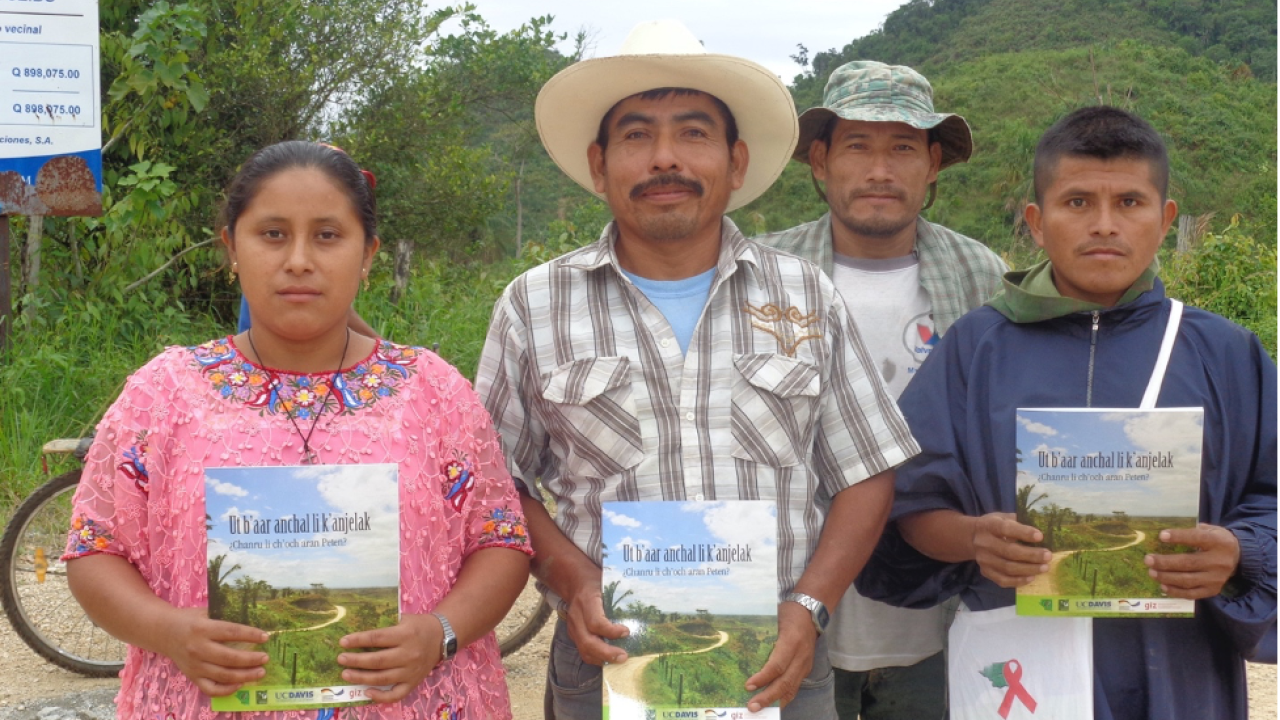

The World Bank had refused to provide the modest amount of funds that were needed to return the results to the villages, so I used some of my UC Davis start-up funds in 2012 to print 2,000 reports in colloquial Spanish and Q’eqchi’.

Over 2014 (the first year of the Xeel initiative), ACDIP organizers held almost 200 village meetings across northern Guatemala to disseminate these booklets and discuss what the research meant. As a custom deeply tied to planting, the concept of Xeel apparently sparked deep conversations in the villages about how to hold onto the leftovers— that is, the land still under Q’eqchi’ control.

Birds-eye View Sparks Discussion

Using our data villagers began analyzing the birds-eye view of the deforested landscape and enclosure by cattle ranching and pesticide-intensive plantation agriculture. This led to spontaneous discussions in numerous villages about how to restore the agro-ecological productivity of lands still under smallholder control. Communities expressed a hunger for more information on agroforestry, revitalization of heirloom maize, tree canopy crops like cacao orchards, home gardens, mulches, natural pesticides, intercropping, biochar, nitrogen-fixing cover crops and other forms of organic agriculture and reforestation. They asked their leadership to start agroecology education programs for their youth, so they might have a sustainable future in farming.

A Revived Mission

In short order, ACDIP has shifted its mission from securing private land title to pursuing a new mission of reconstituting communal land tenure and agroecology. Through a racial discrimination lawsuit against the government, the federation secured funds to open an accredited Q’eqchi’-language high school (INDRI, the Institute for Rural Integrated Development of Peten), now educating 200 youth toward a degree in rural community organizing. Their membership exploded from 32 to162 villages. Within a few years, a hundred of those villages have declared themselves “autonomous indigenous communities” and re-established ancestral village councils.

As described in my other blog (see part two), with seed funding from the UC Davis Academic Senate, I have been collaborating with ACDIP’s spiritual elders to document the sacred sites lost to land grabbing and to co-develop a plan for reclaiming and reforesting those areas. This autonomous Q’eqchi’ region now connects a tri-national arc of Maya autonomy from Zapatista territory in Chiapas to the constitutionally-declared Maya homeland in southern Belize. As ACDIP's leader, Jose Xoj reflected, “That study continues for us…. your hair and my hair may now be gray, but that study will live on.”

Approaching ten years after that first World Bank study, I dialogued with ACDIP’s leadership about replicating the mapping exercise under their own auspices to measure the impact of community organizing in slowing land sales. In August 2019, we planned a slightly different methodology that would differentiate between voluntary internal land transfers (Q’eqchi’ to Q’eqchi’) and more coercive sales to land grabbers. A generous graduate student, Kenji Tomari, programmed a method to overlay the cadastre onto free Google Earth imagery, instead of the outdated and expensive NASA satellite, and overflight data we had used for the World Bank study.

Pandemic Pause Motivates Training of Youth

Covid-19, unfortunately, interrupted our plans. In consultation with their spiritual elders, ACDIP’s leadership proposed that we use, what we called “the pandemic pause,” for a safer project to train their youth in cadastral mapping for demarcating communal lands. In partnership with a Q’eqchi’ organization to the south, APROBASANK, with a Q’eqchi’ cartographer, 10 carefully selected youth learned practical GPS skills and participated in critical discussions about the relationship between communal land tenure and Q’eqchi’ cultural values of reciprocity. Once they acquire a Trimble geospatial unit, ACDIP will no longer depend on Spanish-speaking technocrats for maps. It will also allow us to begin demarcating their three best-organized villages, which have already won legal resolutions to re-title their lands collectively.

As a cultural anthropologist, I feel fortunate to have been able to continue this work as a far-afield ally during the pandemic because, like the concept of Xeel, I have consistently reciprocated my work —whether through film, popular comic books, radio soap operas, or village maps — to the communities and leaders who collaborated with my research and beyond. Decolonizing research demands that public-interest scholars share out work through non-academic fora regardless of whether it counts for merit or promotion.

Learn more about their PIRI Grant Project

Read part two.

All blogs are the personal accounts and opinions of the individual writers and do not necessarily reflect the those of Public Scholarship and Engagement or UC Davis.