Open Letters from Prison

Responding to COVID-19 in Prisons by Mobilizing Communities of Collective Care

The first documented case of COVID-19 in California was on January 26, 2020. It soon spread to California prisons, where outbreaks and lockdowns wreaked havoc. This new threat facing people inside prison could only be dimly imagined by loved ones, friends and allies on the outside, who were cut off from usual visitation and other forms of communication, including JPay, email and phone calls. Within months, reports of new quarantine units — such as Building 503 at the Central California Women’s Facility, “the world’s largest women’s prison,” — made it clear that prison guards, along with California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) policies and practices, were enabling the spread of the deadly virus. The use of medical lockdowns to control and punish further endangered people’s lives. Women in prison, like longtime California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) member Laura Purviance, described the lockdowns as being similar to solitary confinement. People inside felt so unsafe, Purviance told reporters, some asked family members to take out life insurance policies on them.

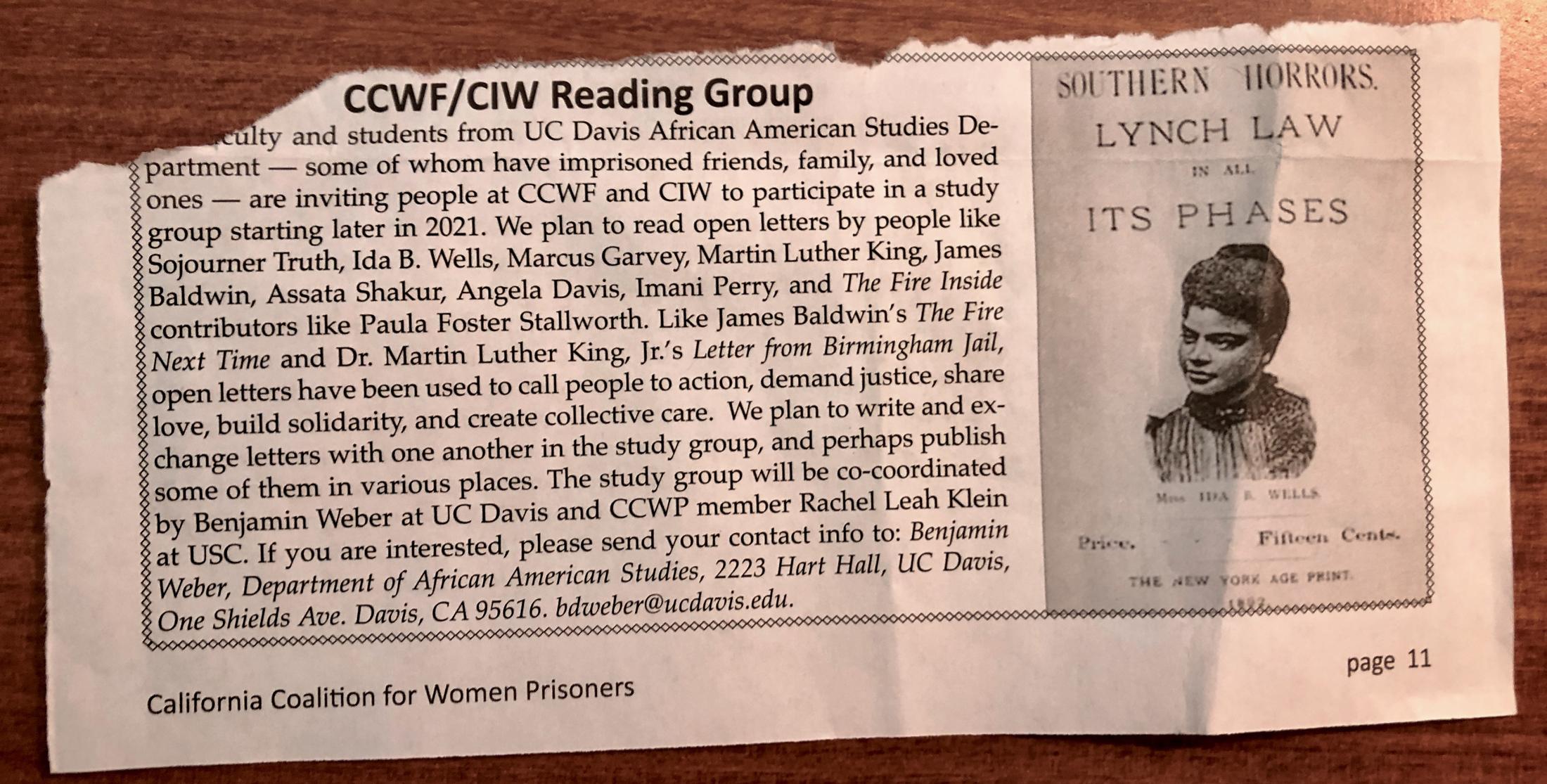

CCWP’s emergency COVID-19 response was in full swing when Benjamin Weber, assistant professor of African American and African Studies at UC Davis, reached out to CCWP organizers to see what he could do to help. Two members of CCWP’s The Fire Inside prison newsletter editorial collective, Pam Fadem and Rachel Klein, put the question to incarcerated CCWP members. With time in lockdown extended, in-person visitation completely closed down, and email and phone time drastically reduced, people in prison had returned to writing more handwritten letters. Under COVID-19, women in prison were looking for a mental escape, ways to sustain connections and community, and an outlet to process and advocate for issues at the foreground both inside and outside the prisons. Since The Fire Inside already circulated through the postal service, the idea for a letter correspondence group clicked. Together they put out the call for an “Open Letters Writing Group” in December 2020 issue of The Fire Inside, inviting people to study famous open letters in Black history and write in the style of authors such as Ida B. Wells, Claudia Jones, Maya Angelou, Assata Shakur, Angela Davis and Alicia Garza.

A host of individuals from prisons around the country responded, and 20 incarcerated individuals requested to join — seventeen women and three men. Over a year-long process, members of the Open Letters Writing Group wrote reflections about published open letters, exchanged feedback, and then composed their own open letters inspired by those they studied and as a call to action. Grounded in a Black studies approach to collective storytelling, the writing group used modes of horizontal feedback, reflection and collaboration in studying the past to write personal narratives about the present and future.

We chose the theme of collective care, thinking through how open-letter writing contributes to that modality, especially in times of COVID-19, when access to community for so many incarcerated peoples has been cut off. As written in The Fire Inside, “Collective care, mutual respect, resilience, and determination, are the foundations of our community, where our strength and power are built and sustained.” This commitment and practice animated the work of the Open Letters Writing Group across six different prisons. Collaborator Joyce Schofield emphasized this mutuality in her open letter, writing, “Spending decades incarcerated and away from my children doesn’t stop me from being happy when another inmate is released and walks out these gates of hellish agony and mental suffering, into the loving arms of their loved ones.” Schofield concluded with a resolute call to solidarity: “I embrace every woman, be she behind bars or in the free world. I invite you to take whatever steps necessary so that you too can become A WOMAN WITH A MADE UP MIND!” Another writing group member, Delina Williams, affirmed this invocation of collective care in her response to Joyce’s open letter, writing, “‘A Woman with a Made Up Mind’ is not only riveting, it left me shaking my head in agreement throughout its entirety.”

The letters flowing back and forth across prison walls demand to be seen as a process of community building and as collective acts of rebellious reciprocity. They are expressions of hope, aspiration and love. Feedback from the Open Letters group members attested to the transformative power of their writing. Williams wrote, “I needed, even now, to send forth this letter of love.” She saw it as a “respite from this lockdown.” Williams was not alone. While reflecting on various moments of the open-letter writing project, each member spoke of the generosity and reciprocity that emanated from each other. For Lety Zepeda, it added “positivity to a sometimes dark place.” Laura Purviance recognized the potential “to use this as a form of restorative justice — to use collaboration and conversation for healing and growth.” Along those lines, Joyce Schofield wrote, “Being 70 yrs old, this gives me the peace I need in case I don’t make it home, maybe I will still reach and help others.” For Tamara Hinkle, the feedback from her peers made her emotional. “Their encouragement is validation,” she wrote. “Words are empowering motivators spoken to uplift those in need.”

At the end of this first round of the writing group, members requested certificates of completion, and we collectively agreed to publish a special issue of The Fire Inside featuring the open letters. This was less as an academic accolade and more as an acknowledgment of individuals’ accomplishments that could be listed in their parole files. Partnership and collaboration, learning from and alongside each other, and revising and improving their work based on feedback from other incarcerated members were the building blocks of this project.

There’s a saying in social movement circles that work “moves at the speed of trust” and in this case our strong connection was built through the sustained commitment of time, energy, resources and genuine care for one another. The importance of two-way learning and the exemplar of collective care on an everyday scale are vital lessons from which to learn, especially in the United States. Pinpointing this very mutuality, Delina acknowledged how, through creativity and collectivity, “this program allows like-minded persons to encourage others to be more than a number. To be free through the writings of our truths as we share our scars, insecurities, as well as our capacity to grow.” Breaking the scarcity logic that governs and infects everything from our institutions to our social relations, collectivity articulates a different value system through which justice may actually be possible, according to Delina Williams. As she contended, “Collaboration is information and when used to propel justice, kindness and peace, we are on our way to a society that sees past what we once were and allows us, as people, to seek a place at the table not under it.” We have much to learn.

────

Learn More About Public Impact Research Initiative

- If you want to learn more about Assistant Professor Benjamin D. Weber's work, here is his project summary.

- Recipients of a Public Impact Research Program grant will receive $5,000 to $10,000. Learn about our application process.

- Public engagement is all about people. Read other stories.

About the Author

Benjamin D. Weber

Assistant Professor

African American and African Studies